DOJ, RI Spar Over Contempt In Olmstead Case

/Federal Courthouse in Providence

By Gina Macris

The state of Rhode Island told a judge it cannot be held in contempt of a 2014 civil rights consent decree seeking to integrate adults with developmental disabilities in their communities because of circumstances beyond the state’s control.

But the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) says that the state has only itself to blame for its failure to comply.

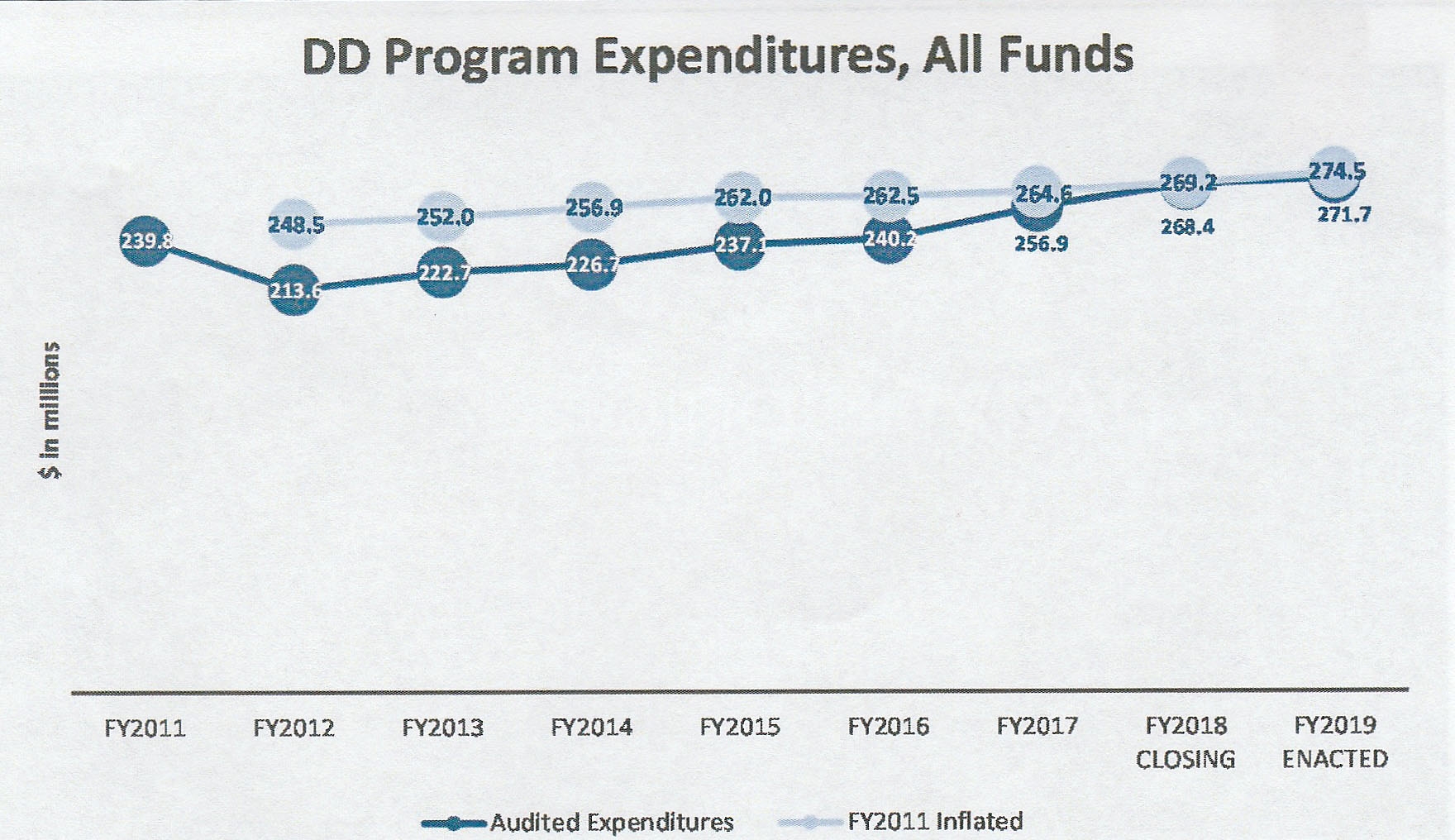

The state’s “persistent choices to under-fund the system have created a dramatic provider shortage” that has left the target population isolated, the DOJ said in a counter-argument submitted Friday, Sept. 10, to the U.S. District Court.

The “refusal to adequately fund the Consent Decree is precisely the kind of self-imposed inability to comply” that undermines the state’s arguments in its defense, the DOJ said.

The decree stems from a 2014 finding by the DOJ that the state violated the Americans With Disabilities Act by relying too much on sheltered workshops paying sub-minimum wages and isolated day care centers, which kept people with disabilities out of mainstream society. The Olmstead decision of the U.S. Supreme Court has re-affirmed the rights of people with disabilities to receive support in their communities to give them a chance to live regular lives.

The DOJ further cites warnings of an independent court monitor a year ago that the state will be unable to comply with the consent decree by 2024 unless it came up with a multi-year plan to overhaul its developmental disabilities system, which for a decade has encouraged segregated care over integrated services. Such a plan has not been forthcoming.

The state’s lawyers, Marc DeSisto and Kathleen Hilton, submitted arguments Sept. 1 in response to a DOJ motion two weeks earlier that asked the Chief Judge of the U.S. District Court to find the state in contempt of the consent decree and impose fines ranging up to $1.5 million per month. Chief Judge John J. McConnell, Jr. has scheduled a hearing the week of Oct. 18 through Oct. 22.

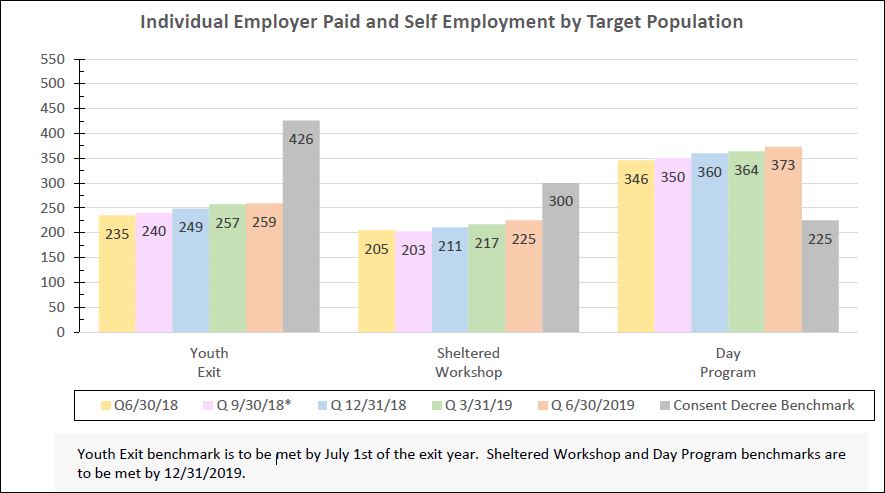

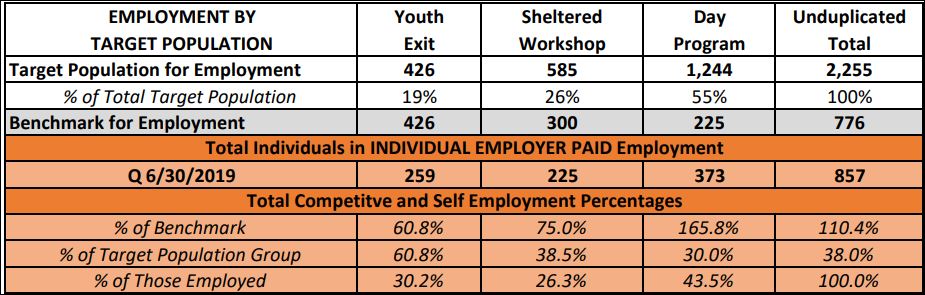

The state’s lawyers maintained the state could not meet benchmarks for integrated employment and other criteria because of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as resistance by adults with developmental disabilities themselves to work and non-work activities in the community.

But in its reply Sept. 10, the DOJ said the state’s characterization of the population “paints an inaccurate and offensive picture of people with developmental disabilities” and “reflects a profound misunderstanding of the nature, purpose, and obligations of the Consent Decree.”

DeSisto and Hilton, meanwhile, also argued that numerical targets for employment of adults with disabilities were not required by the consent decree, even though, as the DOJ said, documents show that state officials have admitted the opposite in numerous statements to the court since 2014, in writing or in person..

The state’s lawyers also maintained the state cannot be held in contempt until after the agreement expires on June 30, 2024 – an interpretation the DOJ said is unheard of in litigation involving system-wide reform.

In picking apart the state’s position over 28 pages, the DOJ said the state is urging the court “to adopt an interpretation of the consent decree that is “at odds with the decree’s text and purpose,” the DOJ said.

The state maintained the consent decree “imposed what could only be described as a cultural shock on the targeted community. After years of receiving services in “non-community” settings, “they are being told that their lifestyle must change,” the state’s lawyers said.

The DOJ disagreed. Rather than being told what they must do, the DOJ said, those eligible for services and their families have the right to make informed choices after receiving education and support about what working and enjoying leisure activities in the community might mean for them.

The state’s own data show that it “dramatically overstates” the resistance to integrated services, with 80 of 1,877 persons, or 4 percent, opting out of integrated services through a formal variance process, the DOJ said. And it cited a report from a court monitor in 2016 who had said he found “strong broad-based acceptance of the goals and desired outcomes of the consent decree.”

Similarly, the DOJ lawyers rejected the state’s argument that the COVID-19 pandemic prevented compliance with the annual employment targets in the consent decree. The pace of new job placements had slowed significantly more than a year before the onset of COVID-19, the DOJ said.

While the pandemic did make compliance more challenging, the state made “minimal efforts” to serve the consent decree population during the pandemic, the DOJ’s civil rights division argued.

“Given the availability of enhanced federal matching funds for providing integrated Medicaid services like those the Consent Decree requires, the State has the opportunity to increase funding for integrated employment services, provide the full amount of integrated day services to each target population member, and enhance wages to attract the required number of service providers,” the DOJ said. Its memorandum is signed by Rebecca B. Bond, chief of the DOJ’s civil rights division, as well as trial attorneys expected to litigate the case in October.

The state did earmark $39.7 million in federal-state Medicaid money to raise the wages of workers and their supervisors by $2 to $3 an hour in the current budget, a roughly 15 percent increase, but only at the conclusion of court-ordered negotiations between state officials and providers.

DeSisto and Hilton, the state’s lawyers, also said the state is finalizing the language in a request for outside proposals “for evaluation and implementation of new rate and payment options for (the) Developmental Disabilities Services System.” The preparation for the request for proposals indicates that BHDDH plans to go out to bid through the state purchasing system, which can take several months.

The state last conducted a rate review in 2010 and 2011, but the General Assembly did not follow the recommendations of the consultant, Burns & Associates. Instead, it set dozens of reimbursement rates for private providers roughly 17 to 19 percent lower than Burns & Associates recommended, with the Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH) saying that it still expected providers to maintain the same level of service.

In November 2018, a principal in Burns & Associates, Mark Podrazik, testified before a special legislative commission that that a rate review was already overdue. Rates should be reviewed every five years, he said.

A few months later, BHDDH hired NESCSO, the nonprofit New England States Consortium Systems Organization, to analyze Rhode Island’s developmental disabilities system from top to bottom.

Although the NESCSO contract called for a rate review and analysis of alternatives to the state’s fee-for-service reimbursement system, NESCSO was asked to present options for change but to make no recommendations.

The BHDDH director at the time, Rebecca Boss, said the department wanted to expand its analytical capability and make its own choices going forward.

The 18-month contract, which cost $1.1 million, produced a final report and supplementary technical materials which, among many other things, said the provider system was significantly underfunded. Since the report was completed July 1, 2020, BHDDH has remained silent on its findings, and has not exercised options for renewal of NESCSOs services.

In their memorandum, the state’s lawyers said that “the intention of the rate review process is to strengthen the I/DD system and services provided to individuals, as well as to address provider capacity to deliver those same services. Thus, the State can and will at hearing clearly demonstrate that it has been ‘performing its obligations’ under the various sections of the Consent Decree.”

The DOJ has scoffed at that notion. The DOJ said in its original filing in August that it is prepared to show the “State failed even to ask its Legislature for a sufficient appropriation, and that the State failed to make efficient use even of the resources it had – for example, by failing to modify State rules and incentives that favor providers of less integrated services over providers of more integrated services.