RI Project Sustainability's Plan For Enhanced DD Services Was "Cover" For Budget Cuts - Testimony

/By Gina Macris

Louis DiPalma, Chairman of Project Sustainability Commission Photo By Anne PETERS

Project Sustainability, introduced in Rhode Island in 2011 as a method for enhancing individualized services for adults with developmental disabilities, instead has diminished the quality of their lives.

That assessment set the stage Oct. 9 for deliberations of a Senate-sponsored commission charged with studying Rhode Island’s past and present system of developmental disability services, with the aim of designing a better future.

At the same time, the chairman of the 19-member panel, Sen. Louis DiPalma, D-Middletown, emphasized that the purpose of the commission is not to assign blame but to learn from the past and present to figure out how to best move forward. The commission must report to the Senate by March 1.

Project Sustainability was “a well-manicured statement to cover up” cuts in funding and services, said Tom Kane, CEO of AccessPoint RI, one of three dozen private agencies serving adults with developmental disabilities in Rhode Island.

Kim Einloth Testifies

Project Sustainability had a “major impact on the quality of service we were able to deliver,” said Kim Einloth, a senior director at Perspectives Corporation, one of Rhode Island’s largest service providers. She said the community-based program of day services was forced to put people in large groups, lay off specialists like occupational and speech therapists and discontinue consulting services with physical therapists.

Gloria Quinn, executive director of West Bay Residential Services, said she noticed immediately that the disabilities system was “demoralized, decreased and degraded” when she returned to Rhode Island after a nine-year absence in 2013. When Quinn moved out of state in 2004, she said, Rhode Island was one of the top-ranked states nationwide for its programs for adults with developmental disabilities. Quinn sits on the commission.

In a meeting that lasted about 90 minutes, the commission covered a broad range of topics related to Project Sustainability and the controversies linked to it: inadequate overall funding, depressed worker wages, and an assessment used – or misused - to determine individual allocations for services.

The planning and execution of Project Sustainability has been well documented, primarily by Burns & Associates, healthcare consultants hired by the Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH) in 2010.

DiPalma said that from what he’s seen, Burns & Associates was “charged with providing a plan, and the state chose to do something different.”

Rebecca Boss, the current director of BHDDH, reviewed the history of Project Sustainability, designed to bring uniformity to funding for specific services and enable families to make informed choices about services. Project Sustainability aimed to use data gathered through new funding methods to create incentives for services to be delivered in the most integrated setting possible, she said.

“Change is hard, and even with perfect planning, it would not result in everyone’s needs being met,” Boss said.

“I think everyone knows” that the current administration – including Governor Gina Raimondo, Kerri Zanchi, the Director of Developmental Disabilities, herself, “is committed to working with our stakeholders” to figure out “where do we go from here,” said Boss.

“Many may have different views of history, as is often the case,” said Boss, a commission member.

Kane, of AccessPoint, said he didn’t want his anger about Project Sustainability to reflect the way he regards the current administration. The working relationship service providers now have with the BHDDH administration, he said, is “better than we’ve had in a very, very long time.”

Tom Kane Chats After The Commission Meeting

The plans for Project Sustainability “talked about individualizing services and moving toward person-centeredness and all of the lovely buzz words,” said Kane, but the rhetoric really described “a system we already had that got dismantled.”

While Project Sustainability talked about individualization, inclusion and community support, the regulations governing developmental disability services “were always about center-based group activity.”

“Finally, under this administration, the regulations have been put forward that will put back the flexibility we need,” Kane said. The new regulations have passed a public comment period and are to be finalized by the end of the year.

Funding, however, has a long way to go to support the kinds of changes providers, families, and consumers want, by all accounts.

Commission member Andrew McQuaide zeroed in on historical funding of developmental disability services.

McQuaide said that developmental disability spending had been on a downward trend in Rhode Island since 1993.That was the year before the last residents left the Ladd School, the state’s only institution for those with intellectual challenges.

Citing According to Burns & Associates, McQuaide said:

Between 1993 and 2008, Rhode Island’s expenditures for developmental disabilities decreased by 29.5 percent at the same time the national rate increased by 17.8 percent.

Rhode Island is only one of 14 states to report a reduction between 2007 and 2009 in per-person expenditure, a decrease of 4 percent at the same time the national trend registered a 5.6 percent increase.

McQuaide also said that anecdotal information indicates about half the state’s private providers were reporting operating deficits in 2009, ill-preparing them to absorb the additional funding cuts that came along with Project Sustainability.

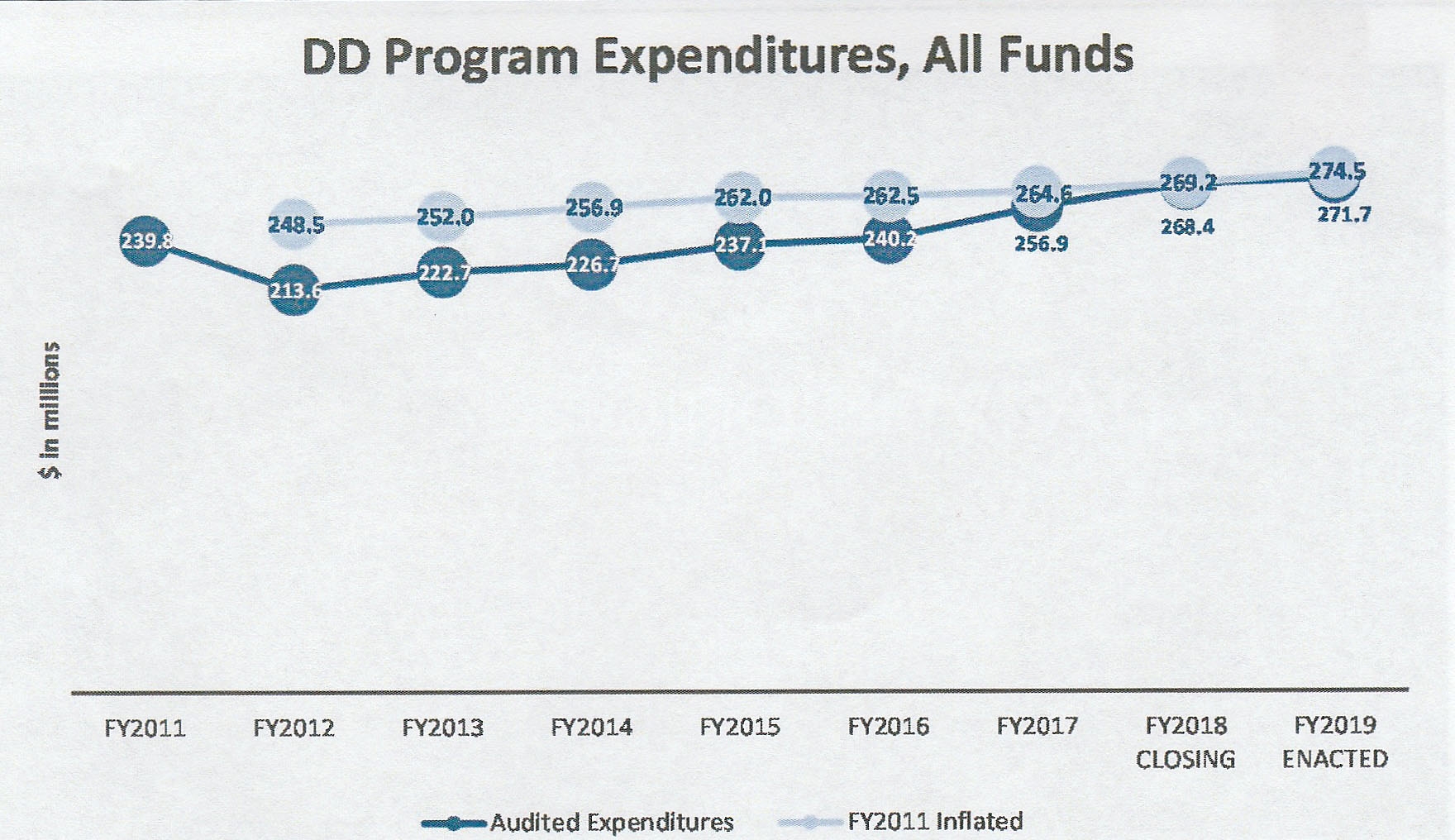

An overview prepared by the Senate Fiscal Office showed that actual spending on developmental disabilities, including both state and federal Medicaid funds, dropped $26.2 million in the fiscal year that began July 1, 2011 when compared to spending during the previous 12 months.

The overview shows that, adjusted for inflation, the current budget still has not caught up to the spending reach of the developmental disability system in the year before Project Sustainability was enacted.

Chart courtesy of RI SENATE FISCAL OFFICE

Prior to Project Sustainability, private agencies negotiated an annual sum for each individual in their care.

The new system generated standard reimbursement rates for each of 18 different services that agencies were authorized to provide.

Kane noted that from the outset, the funding for Project Sustainability was not designed to cover all of the actual costs of private providers, almost all of whom had submitted extensive financial data to the state.

A BHDDH memo for rate-setting that the department sent to the General Assembly noted that the reimbursement rates eventually adopted for Project Sustainability were 17 to 19 percent below “benchmark rates” which Burns & Associates calculated from the median wage for direct care jobs - $13.97 an hour.

The state could not afford more, the memo said, citing the poor economy at the time.

The memo said the lower reimbursement rates were calculated by reducing the allowances for fringe benefits for workers and in some cases, cutting transportation and program expenses.

Kane, who is familiar with the rates in the memo and other Burns & Associates documents, said providers were “actually told in a meeting, ’We’ll see what this (the benchmark wage) costs but we won’t actually bring this to the legislature because they’ll laugh at us.’

“I don’t understand why the expenditure of well over a million dollars on Burns & Associates wasn’t taken seriously enough” to put forward actual expenditures “and let the legislature decide whether it was appropriate,” Kane said.

McQuaide, meanwhile, quoted from the memo. “We did not reduce our assumptions for the level of staffing hours required to serve individuals. In other words, we are forcing the providers to stretch their dollars without compromising the level of services to individuals,” the memo said. See related article

McQuaide said the experience of the last seven years has shown that it was a “fiction” to think the system of private providers would be forced to implement Project Sustainability without compromising services.

The state has a separate system of group homes for adults with developmental disabilities which has not been subject to rules or the pay cuts that came with Project Sustainability. Instead, the workers are unionized state employees with full benefits.

Donna Martin and Andrew McQuaide

In the privately-run system, McQuaide said, the wages paid direct care workers still don’t reach the original $13.97 per hour “benchmark”, or median-pay rate, calculated by Burns & Associates.

The most recent data available indicates that the average entry wage for direct care workers is $11.37 an hour. It comes from a survey of member agencies of the Community Provider Network of Rhode Island (CPNRI) conducted last February, according to Donna Martin, executive director of the trade association, which represents about two thirds of service providers in Rhode Island. Martin said she is in the process of updating the figure.

Martin, a commission member, told the panel that CPNRI has met with the BHDDH leadership and representatives of Governor Raimondo’s office and the Office of Management and Budget to review current provider reimbursements in comparison to an extensive menu of rates envisioned by Burns & Associates in planning Project Sustainability. BHDDH, OMB, and the Governor have already planning a budget proposal for the next fiscal year.

DiPalma said Burns & Associates originally wanted to advance a “competitive” average wage of $15.46 an hour.

Addressing wage inequities will be a critical focus of the commission’s work, he said. Two years ago, DiPalma started a campaign to raise direct care wages to $15 an hour over five budget cycles. Massachusetts already pays its direct care workers a $15 hourly rate, and many Rhode Islanders find they don’t have to move to take advantage of these higher-paying positions at agencies that are an easy commute from their homes, DiPalma said.

Another source of rancor over the last several years has been the assessment used to determine individual funding levels under the terms of Project Sustainability – the Supports Intensity Scale (SIS), which was updated in November, 2016.

Kane has said data compiled by Burns & Associates indicate the original version of the SIS was used to cut individual funding. See related article

A. Anthony Antosh

Even though the SIS has been revised, the state’s top academic researcher in developmental disabilities, A. Anthony Antosh, told the commission that using the SIS as a funding tool violates the original intent of the instrument as an aid for professionals designing individual programs of support for persons with disabilities.

Antosh, a commission member, is the retiring Director of the Sherlock Center on Disabilities at Rhode Island College.

His comments apparently prompted Kane to recall another moment in a Project Sustainability planning meeting in which Burns & Associates’ human services partner praised the multi-faceted assessment providers were using at the time to figure out how much funding a particular person needed. In each case, the assessment took into account intellectual capacity, responses in various situations and potential risks.

That Burns & Associates partner, the Human Services Research Institute of Oregon, wrote a memo to the General Assembly saying that “ ‘resource allocation’ should never be thought of as mostly an exercise involving the assessment and simple service delivery.”

Policy makers should also take into account the goals of the programs, such as increasing community integration or increasing employment, before determining the array of services and rate schedules, HSRI said.

“Data collected by a measure such as the SIS is necessary,” the memo said, “but certainly not sufficient.”

The memo was condensed before it reached the General Assembly, and the recommendation against using the SIS alone to determine individual funding was eliminated,