“If anybody couldn’t tell, I am obsessed with the issue of funding as essential for us to get there,” McConnell said during a virtual hearing in July.

“If we don’t come up with a way to systemically support the (service) providers, then the whole thing will be meaningless,” McConnell said.

He has said he is prepared to tell the state to “find the money” to comply with the consent decree. State officials who control the purse strings must participate in the redesign of services, the judge has said.

In the most recent monitor’s report, Antosh set the tone for his recommendations by saying that compliance is “not found in a narrow analysis of the benchmarks of the Consent Decree, but is rooted in defining the structural changes that need to occur in order that the goals of the Consent Decree can be achieved.”

In bold print, he highlighted the fact that the outside analysis of the existing system found that most of the private service providers are “fragile and profoundly undercapitalized.”

In a separate report, the state responded to a court order that it address 16 fiscal and administrative barriers to the integration of people with developmental disabilities into their communities as mandated by the consent decree. The summary is the first of six progress reports the state must make to Judge McConnell by next June on its planning effort for long-range reform.

In its report, the state set a deadline of March, 2022 to overhaul its fiscal system. The changes include the elimination of three practices that for years have been identified as problematic by families and providers:

staffing ratios that discourage community integration, so that in some cases, one worker must supervise up to five people on an outing, whether or not those people want to be there.

documentation of staff time in 15-minute increments, which providers say diverts significant resources that otherwise could be used for direct services.

Allocation of a certain percentage of services for segregated facility-based activities.

Alluding to the budget uncertainties caused by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, the state’s seven-page summary cautions that the planning efforts are “dependent upon the continuation of current state staffing and budgetary levels.”

Monitor’s Budget For Reform Coming “Soon”

McConnell has asked Antosh to analyze current funding and make a dollars-and-cents recommendation for the cost of implementing the needed comprehensive changes.

Antosh said that report will be completed “soon.” He said he has begun that work, relying primarily on data drawn from an 18-month study done by the New England States Consortium Systems Organization (NESCSO) for the state’s disability agency.

The 143-page NESCSO study presented a number of findings and options for change but made no recommendations, at the behest of the Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals.

Antosh said there is a need for systemic restructuring of existing services and supports, which are now “essentially based on group activities that occur in a blend of facility and community settings.”

The situation is exacerbated by a difficulty in recruiting and retaining high quality staff and by the COVID-19 pandemic, which in emphasizing the health risks of large gatherings has “reinforced the diminishing value of facility-based group services,” Antosh said.

The pandemic also has led to a setback in the progress made in the area of employment for adults with developmental disabilities. In June, as the state was beginning to reopen, only 31 percent of those who previously held jobs were still actively employed, Antosh said. (Some on furlough have since returned to work.)

Among work crews hired for large scale commercial cleaning or laundry operations and the like, only about half were working, he said.

The statistics underline a need for “new and intensified approaches to job development,” he said. “What is needed is a new model for providing supports that is more individualized, community based, and uses funds and supports from an increased variety of sources,” including the state’s Department of Labor and Training, Antosh said.

Family Hesitation About Integration

While the gears of state government are focused on moving Rhode Island into compliance with the federal government’s mandate of integrating individuals with developmental disabilities into the larger community, more than a third of the families with an adult son or daughter who would benefit say they oppose or are not yet convinced that the push toward employment is worthwhile.

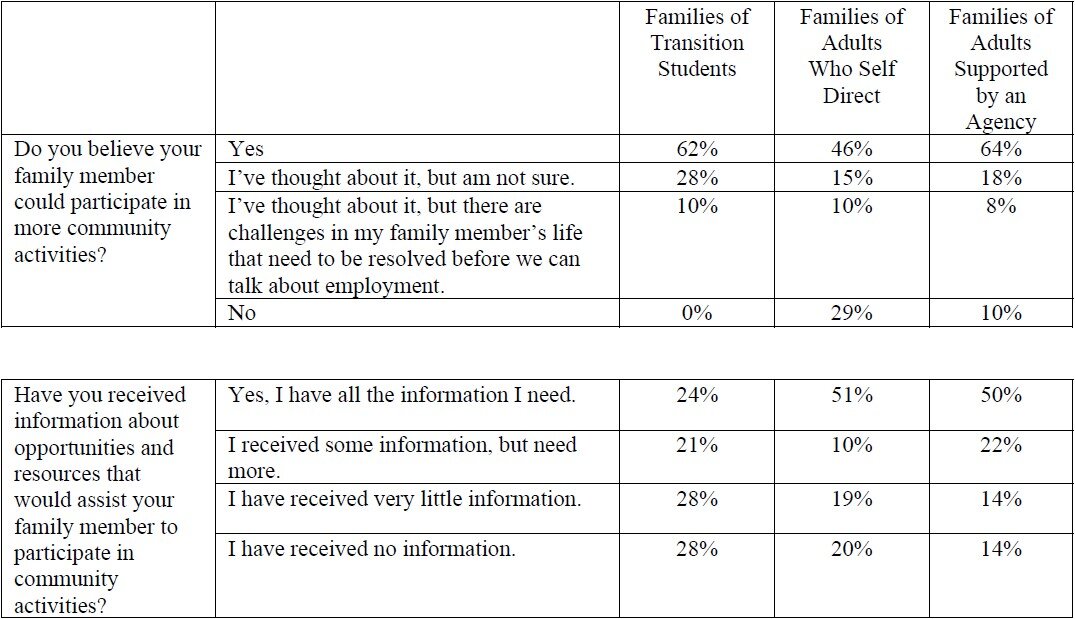

The pandemic aside, significant numbers of families also express opposition or hesitation about their loved ones’ increased participation in community activities.

For Antosh, who included survey results of families as part of his report, the statistics underscore the need for adolescents to experience work-related and social activities in their communities as part of their education and for families to receive more information about the breadth of available opportunities.

It is perhaps most telling that among families of high school students, who are more likely than their older peers to have had internships and community experiences as part of their education, only 3 percent were opposed to jobs for their sons and daughters and 10 percent said they weren’t sure. Two thirds of families of adolescents said they believed the young people should have jobs as adults. Other parents of high school students – about one in five- said their son or daughter had to deal with other challenges before turning to employment. This is typically the case for those with chronic health problems.