$2.5 M Unused For Lack of RI DD Jobs Program

/CVS Trainee - File Photo

By Gina Macris

This article was updated Sept. 10.

A total of $2.5 million dedicated to helping adults with developmental disabilities find new jobs remains unused because the Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals (BHDDH) hasn’t yet decided on a program for spending the money..

A department spokesman has clarified an earlier statement about the amount of money lacking a spending program.

In addition, the Division of Developmental Disabilities (DDD) is still seeking a replacement for the chief employment administrator, who left May 1.

The lack of readily available BHDDH funding dedicated to expanding the number of job placements was disclosed by the Director of Developmental Disabilities at a virtual public forum in August.

The situation represents one factor threatening the promise of a 2014 federal court consent decree to change the lives of people who once spent their days in sheltered workshops or day centers cut off from the rest of the community.

A parallel issue at the top of the list of concerns of an independent monitor is a shortage of skilled workers who assist people with disabilities to find meaningful jobs and expand their activities in the wider community.

The workforce shortage has taken on heightened urgency since the monitor recommended last week that the U.S. District Court accelerate recruitment of workers and possibly impose multi-million dollar fines against the state for noncompliance of the consent decree. (See related article.)

Until a new DDD employment program is adopted, adults with developmental disabilities must either seek state-sponsored employment services funded outside BHDDH or reduce other types of BHDDH service hours to pay for help finding a job.

Limitations on employment supports built into the current developmental disabilities system are part of a comprehensive review now underway of reimbursement rates for private service providers and administrative barriers to integrated services,

The 2014 consent decree anticipated that by 2022 – eight years later – Rhode Island would be scaling up pilot programs of supported employment that would reach some 4,000 people.

But BHDDH has never scaled up. Its first pilot program emphasizing individualized employment supports began in 2016 and underwent several iterations until the final version, the “Person-Centered Employment Performance Program 3.0” ended June 30.

The DDD director announced in February that the program would not be renewed but did not explain the reasons.

At the same time, the director, Kevin Savage, hinted at frustration on the part of the chef administrator for employment services, Tracey Cunningham, saying that she would be “leading the charge” in designing a new supported employment program “if Tracey stays with us, and puts up with us longer.”

But Cunningham, Associate Director for Employment Services since 2016, announced her departure in early April. BHDDH has posted the position twice but has not yet found a replacement for Cunningham.

The BHDDH spokesman could not say why a new supported employment program has not yet been put in place but said the “the DD team is meeting with stakeholders to determine a spending and engagement plan.”

Job Placements Fall Short

In an August 29 report to Chief Judge John J. McConnell, Jr., the independent monitor, A. Anthony Antosh, documented the state’s limited capacity to serve adults with developmental disabilities.

For example, 23 of 31 agencies serving people with developmental disabilities said in a survey they had to turn away clients or stop taking referrals between July and December of 2021 because they did not have the staff to provide services,

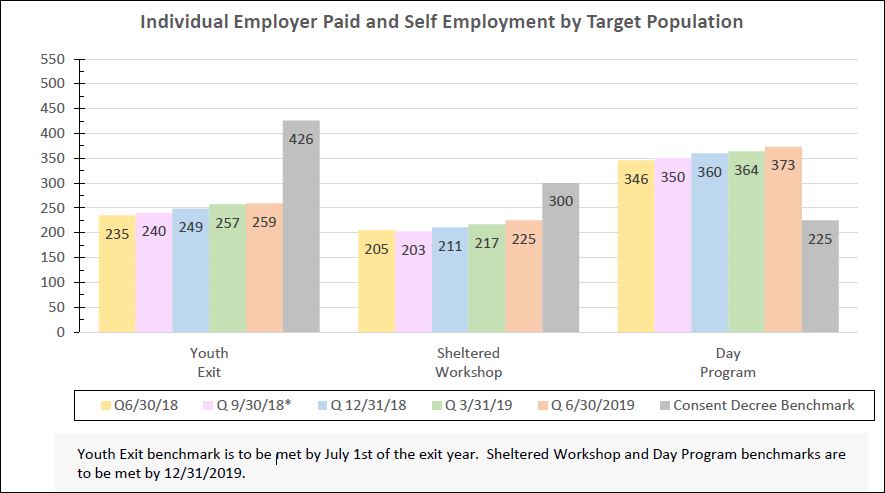

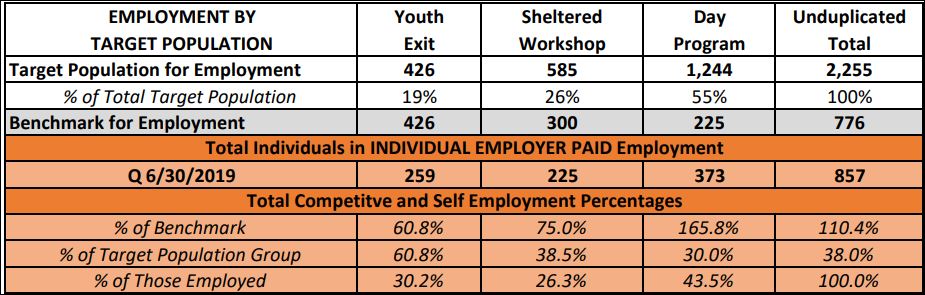

By July, 2022, the state had found jobs for only 67 percent of the consumers that it had promised in the consent decree – 981 of 1,457. (The new-job totals span the entire term of the consent decree, whether or not a particular individual is currently working.)

Antosh said that job placement numbers have remained flat throughout 2021 and 2022, increasing by only 17 in a 12-month period.

In general, he described the developmental disabilities system as being in the “messy middle,” borrowing a phrase from Michael Smull, a developmental disabilities expert on system change.

Antosh said elements of the system desired in the future have been defined, and some individuals are beginning to see progress. But he said most still face the restrictions of the current system, “which needs to be funded and maintained while the future is being built.”

Funding will depend on the results of the ongoing program review that is now underway and how the recommendations will be received by the governor and the General Assembly.

Rate Review To Finish Nov. 1

Under court order, BHDDH moved forward with the comprehensive review, hiring Health Management Associates, the parent company of Burns and Associates, earlier this year. Burns and Associates helped the state a decade ago to implement the current system, which the DOJ found violated the Integration Mandate of the Americans With Disabilities Act. (Burns & Associates says the state did not implement its recommendations for that program.)

The DD director, Kevin Savage, said the review will be completed Nov. 1, a month earlier than expected. He told a public forum in August that he plans to schedule another public meeting shortly after the review is completed to gather feedback from the community before the BHDDH budget goes to the Governor, who must present a proposal to the General Assembly in January.

The review is expected to address not only funding issues but controversial administrative features that the monitor says are barriers to a community-based network of services, starting with the eligibility process.

For a decade, BHDDH has used the standardized Supports Intensity Scale (SIS), a lengthy interview process, to determine the intensity of a person’s disability and assign one of five funding levels for services.

Antosh has pushed back against the state’s stated intention to continue using the SIS, saying it needs yet comprehensive review. Despite the re-training of interviewers in 2016, families still report the SIS does not result in the funding necessary for needed services. And they have complained for years that they sometimes felt humiliated and emotionally drained by the SIS interviews.

The state has developed a supplemental questionnaire intended to improve the accuracy of the SIS, but Antosh said very few families report that they have seen it or understand its purpose.

The families of young people applying for adult services for the first time “continue to report being overwhelmed” by the process, which the state has promised to streamline. And families also generally don’t understand how to appeal a funding decision they believe is inadequate for the services their loved one needs, Antosh said. He recommended that intensive training of social caseworkers continue about communicating new policies to families.

Administrative Barriers To Integration

Antosh’s report also outlined the concerns of service providers about some features of the reimbursement rules, including:

• A requirement that they document the time each daytime worker spends with each client in 15-minute increments, a time-consuming and costly process.

• Another rule that dictates staffing ratios for different kinds of activities, which sometimes results in results in group activities in the community instead of individualized experiences.

Antosh reiterated recommendations of a workgroup on administrative barriers that said:

• The ratios should be replaced with reimbursement rates which allow workers to have 1,2, or 3 clients in their care

• Documentation of worker time should be done in three or four-hour units

Antosh said he expects the reviewers will reach conclusions that are similar to the workgroup. He made numerous other detailed recommendations in the 50-page report.

With the consent decree set to expire in 22 months, on June 30, 2024, Antosh said that all of his recommendations must be “fully implemented with urgency,” using boldface for emphasis.

All the state’s reforms eventually must be approved by the Court.