RI Faces Uphill Climb Halfway Through DD Consent Decree Implementation

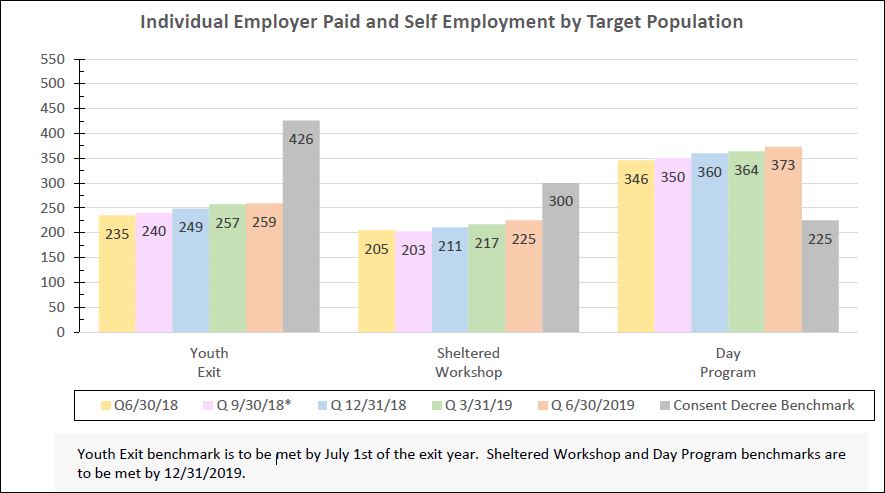

/Bar graph from RI’s latest report to federal court monitor indicates RI is on track to meet one of three categories of employment targets in 2019. “Youth Exit” refers to those those who left high school between 2013 and 2016. “Sheltered Workshop” and “Day Program” refer to persons who spent most of their time in those respective settings when the consent decree was signed.

By Gina Macris

Halfway through Rhode Island’s decade-long agreement with the federal government to ensure that adults with developmental disabilities can work and enjoy leisure time in the larger community:

Rhode Island has linked 38 percent of its intellectually challenged residents to acceptable jobs, prompting a federal monitor to warn that it needs to step up its game

Service providers argue that continued progress will take a larger financial investment than the state is making

Success stories abound but some families remain skeptical about whether the changes will ever work for their relatives.

Five years and three months after Rhode Island signed a federal consent decree to help adults with developmental disabilities get regular jobs and lead regular lives in their communities, 857 people have found employment. Yet, 1,398 others are still waiting for the right job match or for the services they need to prepare for work.

The pace of adding individuals to the employed category has slowed dramatically. Only 37 individuals were matched with jobs during the first two quarters of the current year. To meet its overall employment target for 2019, the state will have to find suitable job placements for 199 more adults. That would require a pace in the second half of the year that is five times faster than the first half.

Though the federal consent decree was signed in 2014, meaningful efforts to comply with its terms did not get underway until two years later, when a federal judge threatened to hold Rhode Island in contempt and levy fines if it did not take numerous and precise steps to begin compliance in a systematic way. At that point, state officials were struggling even to come up with an accurate count of the number of individuals protected by the consent decree, so inadequate was its data collection.

The active census of the consent decree population has grown since 2016, when the judge ordered the state to improve its record-keeping and the monitor forced the state Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH) and the Rhode Island Department of Education (RIDE) to look again at special education students who might be eligible for adult services.

The most recent figures show that there are 3,764 intellectually challenged adults active either with BHDDH or RIDE who covered by the consent decree.

Of that total, 211 were employed in the community prior to the consent decree. Some have signaled they don’t want to work, either because they are of retirement age or for other reasons. Nearly 1,200 others are still in school and not yet seeking jobs.

Of the 2,255 adults who must be offered employment over the life of the consent decree, 38 percent have landed jobs.

The figures are re-calculated every three months.

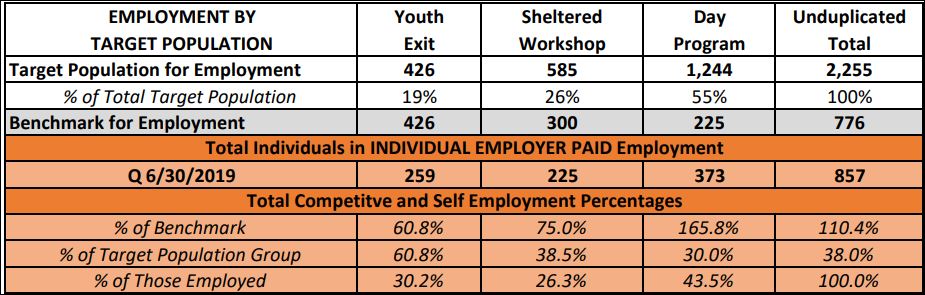

Employment data from the state’s report to the consent decree monitor as of June 30, 2019. broken down by categories of persons who must be offered jobs. “Youth exit” refers to those those who left high school between 2013 and 2016. “Sheltered Workshop” and “Day Program” refer to persons who spent most of their time in those respective settings when the consent decree was signed.

Rhode Island agreed to overhaul its services for the developmentally disabled population after an investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice found the state’s over-reliance on segregated sheltered workshops and day care centers violated the integration mandate of the Americans With Disabilities Act.

People with disabilities have the civil right to the supports and services they need to live as part of their communities to the extent that it is therapeutically appropriate, the U.S. Supreme Court said in the Olmstead decision of 1999, which upheld the integration mandate. In other words, integration should be the norm, not the exception.

Some people couldn’t wait to get out of sheltered workshops when the consent decree was signed and quickly found jobs in the community with a little bit of assistance. But some families with sons and daughters who have more complex needs saw sheltered workshops close without any transition plan. For some of them, the consent decree continues to represent a sense of loss.

At a recent public forum, Kerri Zanchi, director of the Division of Developmental Disabilities (DDD), and Brian Gosselin, the state’s consent decree coordinator, had just finished applauding the successes of those who have found jobs or are on their way to shaping their careers, when Trudy Chartier spoke up on behalf of her daughter.

Trudy Chartier * all photos by Anne Peters

Her daughter is 55, deaf, has intellectual and behavioral problems and uses a wheelchair, Chartier said. She wants a job in the community and she’s been looking for five years.

Her daughter was in a sheltered workshop for a while, Chartier said, and “she loved it.”

“She didn’t care about making $2 an hour,” her mother said, and she made friends there. Now, she said her daughter “is not getting anywhere” and is “so dissatisfied.”

At the age of 80, Chartier said, she doesn’t have the energy she once had to help her daughter change things.

Later, Douglas Porch sounded a similar concern. “I can understand that the idea is to get them into the community, but what it’s actually done is destroyed my daughter’s community, because you’ve taken away her friends.”

“She’s in a group home, with nothing for her to do,” Porch said.

Zanchi, the DDD director, said that the consent decree certainly has changed the way people receive services. The intent is “not to isolate, but the opposite, to build communities,” she said.

“If that’s not working and it sounds like it’s not, we need to hear about that,” Zanchi said. “We can help you so that she can engage with her peers more effectively.”

Another parent, Greg Mroczek, also spoke up. “In terms of all the possible models, isn’t a sheltered workshop for a segment of the DD population the best possible model? Isn’t that what people are saying? It worked for my daughter as well,” he said, and nothing has replaced it.

Kerri Zanchi

He asked whether the sheltered workshop is “off the table” in “any way, shape or form” in Rhode Island.

Zanchi talked about the state’s Employment First policy, which values full integration and“investing in the skills and talent of every person we support.”

“We know that individuals of all abilities have had successful employment outcomes. We also know that employment is not necessarily what everybody wants,” Zanchi said.

“Striking that balance is a challenge,” she said. The state’s developmental disability service system and and its partners are working hard to help meet people’s needs, Zanchi said.

Rebecca Boss

When Zanchi was hired at the start of 2017, she was the first professional in developmental disability services to run the Division of Developmental Disabilities in about a decade.

Zanchi and Rebecca Boss, the BHDDH director, have improved the bureaucratic infrastructure to foster employment, professional development, quality control, and communications with families and consumers and the private agencies the department relies on to deliver services that will meet the monitor’s standards.

For example, the developmental disabilities staff has been expanded and reorganized. An electronic data management system has been introduced. BHDDH invited providers and representatives of the community to the table to overhaul regulations governing the operations of the service providers and has maintained a quality assurance advisory council, with community representation.

Broadly speaking, the leadership of Boss and Zanchi has set the tone for a philosophical shift in which employment is part of a long-range campaign to open the door to self-determination for adults with developmental disabilities – in keeping with the mandates of the consent decree. The state’s last sheltered workshop closed in 2018.

The consent decree also has fostered a revival of advocacy in the community and the legislature, where there had been a vacuum once an older generation of leaders had passed on.

So why isn’t the glass half full at the halfway point in the decade-long life of the consent decree? In a word, money.

Advocates say a central issue is the lack of an investment in the ability of the system to reach more people with the array of services that will open doors and enable them to find their places in the community.

To satisfy the requirements of the consent decree, the state relies on the efforts of private agencies that provide the actual direct services.

The federal monitor in the consent decree case, Charles Moseley, has asked the state to get to the bottom of what he described as a lack of “capacity” on the part of these private agencies to take on new clients.

BHDDH is circling around the funding issue with an outside review of the fee-for-service rate structure governing developmental disability services. That analysis is designed to expand the analytical capabilities BHDDH, leaving the policy decisions to the department leadership.

Advocates for adults with developmental disabilities, most prominently state Senator Louis DiPalma, D-Middletown, say there must be a public discussion about how much money it will take in the long run to complete the transformation from sheltered workshops and day care centers into one that assists people in finding their way in life. DiPalma chairs a special legislative commission studying the current fee-for-service system.

In the meantime, DDD is soliciting a proposal for the third iteration of its performance-based supported employment program, which is designed to focus on people who have never held a job. This group includes young people completing high school and seeking adult services for the first time, as well as adults who face multiple challenges and would find it difficult to fill the standard job descriptions put out by employers.

The new Person-Centered Supported Employment Performance Program (PCSEPP 3.0) is expected to launch Jan.1 with an emphasis on “customized” employment, tailored to match an individual’s strengths and interests with the needs of an employer who is willing to carve up the work at hand in a non-traditional way.

The concept of customization is not new.

In Rhode Island, a few adults with developmental disabilities have had customized employment for many years, most often arranged with the support of their families, who hire staff and direct a unique array of services for them rather than relying on an agency.

In addition, the Rhode Island Council on Developmental Disabilities promotes self-employment, a form of customization, through a business incubator created with the help of the Real Pathways RI Project sponsored by the Governor’s Workforce Board.

The DD Council highlights the products and services of self-employed adults with developmental disabilities as part of its annual holiday shopping event, Small Business Saturday Shop RI, scheduled this year for Nov. 30 at the Crowne Plaza Hotel in Warwick.

The U.S. Department of Labor defines customized employment as a “flexible process designed to personalize the employment relationship between a job candidate and an employer in a way that meets the needs of both. It is based on an individualized determination of the strengths, needs, and interests of the person with a disability, and is also designed to meet the specific needs of the employer.”

Since the supported employment program started in 2017, providers have expressed concerns that, because it is tied to the fee-for-service reimbursement system, it does pay for initial investments the agencies might have to make to participate.

Those concerns persisted during a meeting between DDD officials and potential applicants for the customized employment program in mid July. At the providers’ request, DDD has extended the application deadline to October 4.

Womazetta Jones

The state’s new Secretary of Health and Human Services, Womazetta Jones, has promised to be a careful listener to the concerns of the developmental disability community.

Speaking at the recent public forum, after just eight days on the job, Jones acknowledged the state’s efforts to improve services for adults with developmental disabilities but also cautioned against complacency.

Even though the state has substantially increased funding for developmental disabilities in recent years and gained “stable and effective leadership” at BHDDH, “that doesn’t mean anyone in this room or state government is content with recent progress,” she said.

“The moment we think we don’t have more to do, is the moment we have lost our way,” Jones said, signaling that she is available for further discussion of issues affecting people with developmental disabilities.