By Gina Macris

Educators at Mount Pleasant High School have done a good job integrating special education students with their peers and preparing them for the world of work as adults.

That’s the overall conclusion of a federal court monitor who says the Providence School Department is in “substantial compliance” with a 2013 civil rights agreement which ordered an end to unnecessary segregation of students with intellectual and developmental disabilities, mandating instead an inclusive approach that prepares them to live and work in the community as adults.

The 2013 agreement followed a federal investigation which found that the Birch Academy, a special education program operating within a city high school, was in violation of the Americans With Disabilities Act.

The monitor’s report comes as the state prepares to take control of Providence schools in light of an explosive report by a visiting team from the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy, which found dramatic deficiencies in teaching, learning, achievement and discipline throughout the system.

However, the detailed, 80-page report by the court monitor, Charles Moseley, does not place the school department’s compliance efforts in the context of the Johns Hopkins report or the pending state takeover.

The finding of “substantial compliance” sets the stage for a federal court hearing on whether the city should be granted early relief from federal oversight of the 2013 Interim Settlement Agreement (ISA), which is due to expire July 1, 2020. Even if federal oversight is not curtailed early, the school department was still required to achieve substantial compliance by midsummer of this year to have the agreement terminated as scheduled on July 1, 2020, according to lawyers for the U.S. Department of Justice.

The school department had asked to shorten the length of the agreement months before the appointment of a new state Commissioner of Education, Angelica Infante-Greene, who sent in the Johns Hopkins educators to evaluate the entire school system.

A hearing on the city’s request for early relief is expected in early fall, according to a spokeswoman for U.S. District Court John J. McConnell, Jr., who is presiding over the case.

Moseley said his finding of substantial compliance referred only to the city, and not the state, which is also a defendant in the 2013 case because it licensed a sheltered workshop for adults with developmental disabilities where most Birch students ended up once they left school.

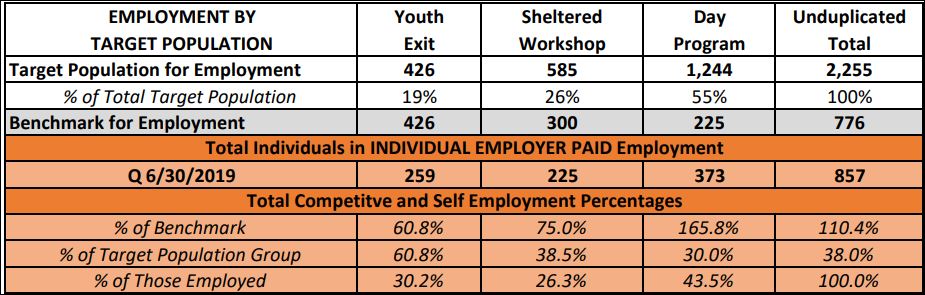

In 2014, after a broader investigation, the DOJ extended the finding of unnecessary segregation to all the state’s sheltered workshops and day care centers for adults with developmental disabilities. The state and the DOJ subsequently signed a separate consent decree mandating a transformation of all Rhode Island’s daytime services for adults with developmental disabilities to an inclusive model over ten years.

Students who leave Birch will continue to receive protections under the provisions of the 2014 consent decree.

‘Culture Of Low Expectations’

Moseley’s report recounted the investigation of the DOJ, which found a “culture of low expectations” at Birch, where students performed menial tasks in a sheltered workshop setting inside the school, often without pay, and were redirected to the work in front of them when they indicated an interest in finding work in the community.

Some students sorted buttons by color into bags or buckets that were emptied by staff at night to be re-sorted the following day, according to the findings.

When students with intellectual and developmental disabilities aged out of the school system, they were sent to a nearby sheltered workshop in North Providence. DOJ found that Birch “served as a direct pipeline” to that workshop, called Training Through Placement. Former Birch students often remained there for decades, even when they asked for a change.

Even before the ISA was signed in June, 2013, Providence closed the sheltered workshop at Birch and replaced the principal, putting the program under the supervision of the special education director. The school department set about redesigning the curriculum with the goal of helping students build skills and confidence to realize individualized post-secondary goals as members of the community at large.

Since 2013, the enrollment at Birch has varied at any given time from 51 to 65 students, according to Moseley’s data.

Moseley praised the redesigned Birch program for its “robust, engaging curriculum;” its efforts to integrate students facing intellectual challenges with their peers throughout the school day, and for providing experiences and activities designed to prepare young people to plan for jobs and otherwise lead regular lives once they finished high school.

In stark contrast, the Johns Hopkins team found a shortage of special education teachers in the system as a whole, with some of them admitting they hadn’t been able to meet their students’ individualized educational goals in years.

Though Mount Pleasant High School was one of the 12 schools visited by the Johns Hopkins observers, their final report does not indicate whether they were briefed on the ISA involving Birch Academy students.

Systemic Improvements Cited

Moseley’s assessment cited improvements in staffing, professional development and leadership, as well as collaboration with the Rhode Island Department of Education and state agencies serving adults with developmental disabilities, particularly in connection with the development of transitional and supported employment services.

One highlight of this type of collaboration has been the creation of Project Search, a work internship program at the Miriam Hospital for students aged 18 to 21. Under this program, the hospital has hired some former Birch students as permanent employees.

Other endeavors offering real-world experiences, including practice in independent living, job discovery and employment –related skills, are the Providence Transition Academy and the Providence Autism School to Tomorrow Academy, Moseley said.

Some Difficulty In Compliance Noted

Moseley noted that the school district has had difficulty meeting two requirements:

Matching each Birch student with two internships before graduation, each one lasting at least 60 days

· Linking students and their families with representatives of adult service agencies, the Office of Rehabilitation Services (ORS) and the Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH).

Of 11 students who were to leave school at the end of the academic year in June, nine had had two internships by the end of February and the remaining two students each had had one. Of those two, one completed a second internship in June. The family of the remaining student, who uses a wheelchair, did not want her using public transportation to go to and from another trial work experience, Moseley reported. He said the school department should have provided the student other options for transportation.

At the end of any given academic year, Providence reported between 51 percent and 91 percent of students preparing to leave school had completed two trial work experiences, although Moseley said this requirement has been met in the “vast majority” of cases.

He said the school department is making “meaningful efforts” to overcome barriers to the internships, such as transportation, irregular school attendance by some students, specific health care needs of others, and, in some instances, parental resistance.

In introducing students and families to adult services agencies, Moseley faulted the school department for not making it clear to parents that they may ask for a representative of either ORS or BHDDH to attend annual meetings for developing the Individualized Educational Plan (IEP) for their son or daughter. The data on attendance at such meetings showed that ORS or BHDDH had a presence only when students were 19 or older, Moseley said. Transitional services are to be made available beginning at age 14, according to the federal Individuals With Disabilities Education Act.

Moseley said the state has agreed to amend the standard IEP meeting notice to give parents the option of requesting ORS or BHDDH attendance. The state has a contract with the private non-profit Rhode Island Parent Information Network to represent the adult service agencies at IEP meetings of students 14 through 17, Moseley noted.

Mosley said that since 2013, the changes made by the city and its school department “have shifted the focus of education and training toward the accomplishments of key benchmarks and provisions of the ISA.”

Assurances of funding and other important changes have grown out of a collaborative approach involving ORS, BHDDH and others that have resulted in memoranda of understandings “with the intention of producing enduring policy change,” Moseley wrote.

He said his reviews over the past few years “have documented the ability of PPSD (the Providence School Department) to maintain compliance with both the letter and intent of the ISA and strongly suggest that such changes will be maintained as ‘business as usual’ beyond the term of this agreement.”