Recent Trend Toward Higher DD Costs Could Upset RI Budget, Directer Tells Senate Finance Panel

/By Gina Macris

Higher costs for providing services to adults with developmental disabilities could lead to “unanticipated stressors” in Rhode Island’s current budget, Rebecca Boss told a Senate Finance Committee subcommittee Sept. 21.

Boss, the new Director of the Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH), also said that for a number of reasons, the department won’t be able to get private-payer reimbursements to offset $3.2 million in Medicaid costs at the Eleanor Slater Hospital as envisioned by the General Assembly when it passed the budget for the current fiscal year.

Boss was one of several human services officials who testified before the Human Services Subcommittee of the Senate Finance Committee about early fiscal projections on Medicaid-funded programs, considered a barometer of the state’s ability to balance the books for the fiscal year which ends next June 30.

Nearly a year ago, BHDDH updated a highly-scripted multiple choice questionnaire used to determine the level of disability – and individual funding – for adults with intellectual challenges. The changes were intended to improve the accuracy of the assessment, the Supports Intensity Scale (SIS).

Although Boss gave no figures, she said the SIS results so far “seem to be trending toward higher acuity” or greater individual needs. If that trend continues, it will lead to “unanticipated stressors in the budget,” she said.

Boss said she would know more after the close of the first fiscal quarter Sept. 30.

State Sen. Louis DiPalma, D-Middletown, the subcommittee chairman, pressed for a specific date when she would have firmer figures. Failing to get one, he set Oct. 15 as a deadline for BHDDH to provide additional information on the budgetary impact of the revised SIS.

DiPalma asked if there is a correlation between increased allocations to individuals and a decline in appeals of SIS results from families and service providers who believe the amount of money awarded is inadequate to fulfill the needs of clients.

Depending on the SIS results, individuals receive one of five funding levels, but appeals, often successful, result in supplemental payments. In the current budget, BHDDH has earmarked $22 million for supplemental payments, which is about ten percent of all reimbursements that go to private service providers. When the BHDDH budget was before the General Assembly last spring, DiPalma said the supplemental payments were too high, suggesting that the underlying funding mechanism was not working.

On Thursday, Boss said there is some correlation between higher funding authorizations and fewer appeals, but part of the trend is that young adults newly approved for services are generally scoring higher on the revised SIS than their counterparts did before the SIS was updated last year. In the cases of young adults, she said, there is no history of appeals.

In response to a question from DiPalma, Boss said a backlog in applications from young adults discovered in 2016 was eliminated and has not reappeared.

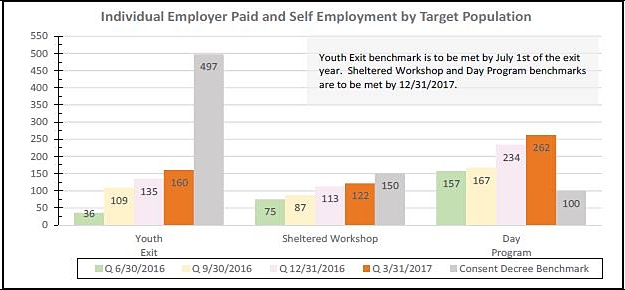

Boss said the increased costs of providing developmental disability services are occurring in the context of a shift toward greater individualization of daytime services and more integrated, community-based residential options required by a 2014 federal consent decree and a new Medicaid Rule on Home and Community Based Services (HCBS).

Daytime services in the community are more expensive because they require more staff than day programs based in a single facility, Boss said.

In connection with costs for group homes for adults with developmental disabilities, Boss projected that BHDDH will “come pretty close” to cutting just under $4 million targeted in the budget, although she added that she could not offer a guarantee.

The $4 million in savings is a “more reasonable target than it’s ever been,” Boss said. Two years ago, BHDDH was expected to cut $16 million from group home costs and saved about $220,000.

Boss said more individuals than in the past are going into shared living with host families in the community or choosing apartment living with some support. The move toward community-based residential options is required by HCBS.

When young adults enter the BHDDH system, group homes are no longer the first choice in residential services, Boss said. .

A newly hired residential coordinator works solely to help people “find the right living environment,” she said.

Boss said BHDDH is having discussions with service providers about the mechanism for disbursing a total of $6.8 million allocated by the General Assembly for higher reimbursement costs that are linked to modest raises for direct service workers, an average of 42 cents an hour.

Direct care workers in Rhode Island make $11.14 an hour on average, according to a trade association of service providers, but Massachusetts has agreed to pay $15 an hour for the same work July 1, 2018.

DiPalma said he feared a shortage of direct care workers would only become worse in the months to come, particularly since Massachusetts is an easy commute for many Rhode Island residents.

DiPalma, who has already called for another wage increase next year as part of a five-year campaign to reach the $15 mark, told Boss he would like to talk about separating the workers’ salaries from the reimbursement rates paid to their employers. Boss said she would happy to talk about it.

The pay increase approved by the General Assembly includes employee-related overhead and benefits costs. Individual employers figure out how much of the overall increase goes into workers’ pockets, although they must document the way they apportion the money.

The raises are to be retroactive to July 1, according to language in the state budget. A BHDDH spokeswoman said recently that the department was “on track” to disburse the money by Oct. 1.

DiPalma emphasized that the low wages in the direct care field exacerbate a gender gap in pay, particularly since many workers are women who are heads of household.

He said the state should look at what it costs in subsidized child care and other forms of public assistance to help support these low-income workers.

Eric Beane, Secretary of Health and Human Services, said that because of structural deficits in the state budget, it’s difficult to find money for priorities such as front-line workers in home care, child care and developmental disabilities, but Governor Raimondo is nevertheless committed to leading a transformation in this important area.