RI "Demanding Dignity" Campaign Backs $15 Minimum Wage For DD Caregivers In Two Years

/RI State Rep. Evan Shanley, D-WARWICK, Left, and George Nee, President of the RI AFL-CIO At the State House Library *** photos by anne Peters

By Gina Macris

Rhode Island State Senator Louis DiPalma and Rep. Evan Shanley say they are introducing companion bills that would set a minimum wage of $15 an hour in two years for those who provide services to adults with developmental disabilities.

The bills were announced at a Feb. 27 State House press conference, hosted by George Nee, president of the Rhode Island AFL-CIO, to kick off a union-backed campaign called “Demanding Dignity” to prioritize a living wage for caregivers in highly demanding jobs who are paid less than fast food workers or retail clerks.

Both Nee and DiPalma said there’s not a single legislator who doesn’t believe that direct care workers are underpaid and have been underpaid for years.

The bills would be costly – an estimated $25 million in state revenue over two years, according to DiPalma.

Nee said the “Demanding Dignity” campaign aims to make the $15 rate a priority for legislators.

The best way to accomplish that aim, Nee said, is to tell and retell the personal stories that convey the impact of the current wage structure on people’s lives.

For him, Nee said, the biggest take-away from the event was the story of Nancy Tumidajski, who works at the ARC of Blackstone Valley in Pawtucket. She said she was hired in 1991 at $10.25 an hour, then double the minimum wage. Today, 28 years later, she makes about two dollars more than that, she said.

By comparison, the minimum wage is currently $10.50 an hour. The average entry-level wage for direct care workers is $11.36 an hour, according to a trade association representing service providers.

Governor Gina Raimondo has proposed raises that would add about 44 cents an hour to workers’ paychecks at a total cost of $3 million in state revenue, that would be roughly doubled by the federal match in the Medicaid program.

L To R: Noelle Siravo, Nancy Tumidajski, Louis DiPalma

Tumidajski said her duties have included resuscitating a client who stopped breathing, performing the Heimlich maneuver – multiple times – on a client prone to choking, and last year, providing hospice care in clients’ own homes when a flu epidemic caused a widespread shortage of beds in the healthcare system. Everyone on her team volunteered for hospice duty, she said.

Noelle Siravo of Pawtucket, the mother of a 47 year-old man with significant disabilities, said he is able to live in an in-law apartment in her home only because of the “wonderful” people who provide him with skillful support and care.

“It’s a tremendous burden off my shoulders,” she said, but “the wages are insulting for what they do.”

In addition to everything else, Siravo said, direct care workers often spend some of their own money on the people they support, because many adults with developmental disabilities don’t have any families and still want an occasional treat.

Tumidajski said one in three workers at the ARC of Blackstone Valley leave their jobs in a year, and the agency has trouble recruiting replacements at pay that runs between $11 and $12 an hour. The ARC currently has 25 vacancies, she said.

The high turnover and vacancy rate threatens the quality of services and safety of clients, Tumidajski said. For the same work, Massachusetts already pays $15 an hour for direct care, and Connecticut has adopted a caregiver minimum wage of $14.75 an hour.

Jeff Perinetti, business representative for the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, the direct care workers his union represents took a 10 percent pay cut when Project Sustainability was enacted and have regained only six percent of it.

DiPalma said the meager wages paid to someone like Tumidajski are unconscionable.

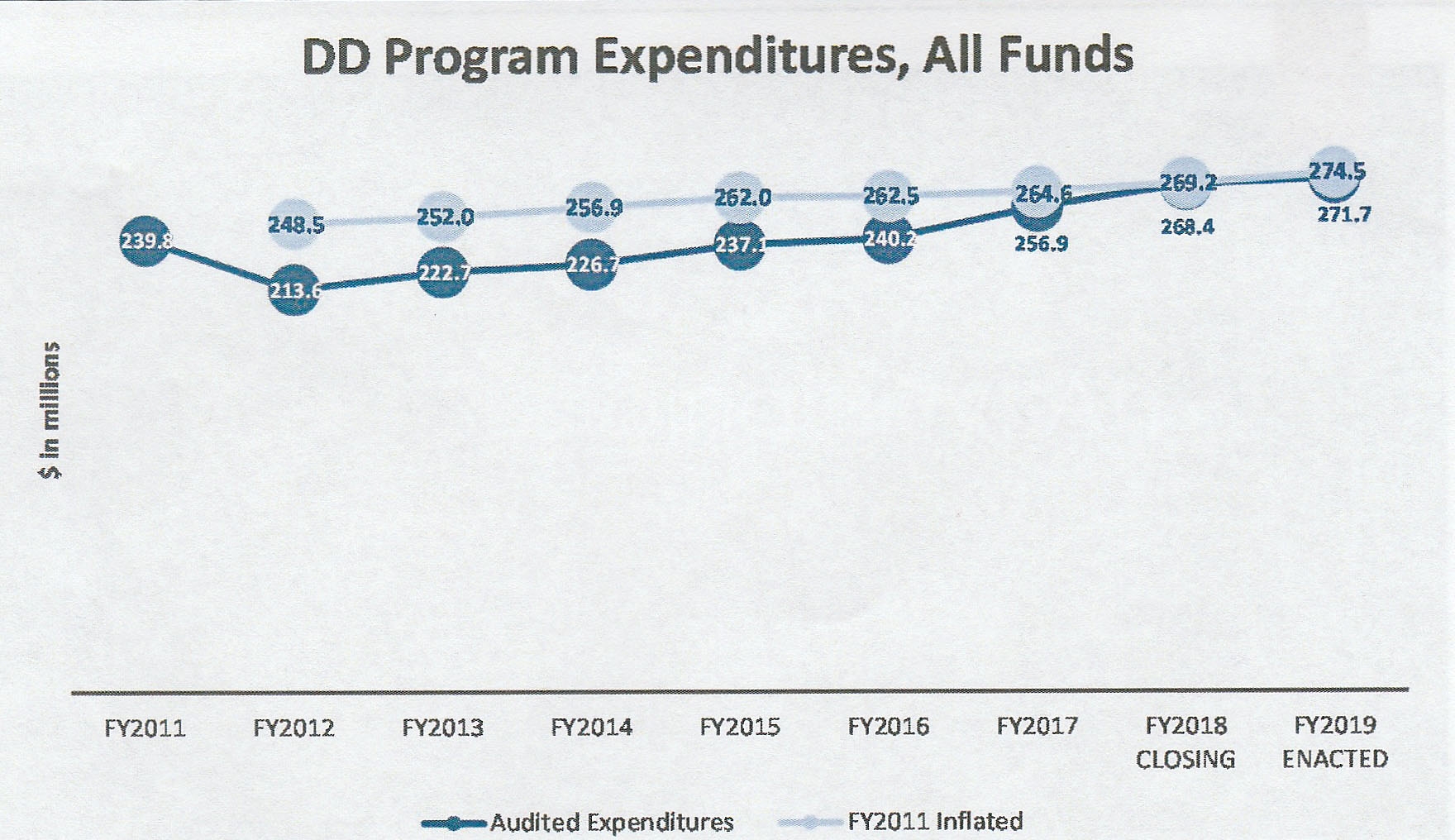

The current rate model, introduced in 2011 with a $26 million budget cut, is built on the backs of workers, DiPalma said.

Established under the title “Project Sustainability, the fee-for-service model brought wholesale wage reductions without scaling back the state’s expectation for developmental disability services from private agencies or establishing a waiting list for services, he said. DiPalma, D-Middletown, is first of the Senate Finance Committee and chairs a special legislative commission that is studying the impact of Project Sustainability.

Shanley, D-Warwick, represents the Cowessett section of the city, which includes the Trudeau Center, one of about three dozen private providers of developmental disability services in Rhode Island and the place where his parents met as they cared for clients who had been stranded during the Blizzard of 1978,

The experience of helping others inspired his father, Paul Shanley, than 19, to become a police officer in Warwick, where he served 26 years, Shanley said. His mother, Mary Madden eventually became President of the Trudeau Center. She has recently been named interim director the Commuity Provider Network of Rhode Island, a trade association of private provider agencies. Both Shanley and DiPalma have previously filed legislation to increase wages for direct care workers.

Jeff Perinetti, business representative for the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, the direct care workers his union represents took a 10 percent pay cut when Project Sustainability was enacted and have regained only six percent of it.

in addition to the machinists’ union, the Demand Dignity campaign is backed by the Service Employees International Union, District 1199; the American Federation of Teachers and Health Professionals, and the United Nurses and Allied Professionals.

Nee set the tone for the event by invoking an enduring quotation from former Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Nee said that Humprey defined the “moral test of a government.” as the “way it treats those in the dawn of life, the children; those in the twilight of life, the elderly; and those in the shadows of life; the poor, the sick, and the disabled.”

“We have an opportunity, with this legislation and this campaign, to determine whether or not Rhode Island , our government, is going to be moving up to meeting that moral test of what government should be,” Nee said.

For too long, people working in the field of developmental disabilities have “too often been relegated to the shadows of our community and our government, and we’re here to say that that should not be happening any longer,” he said.