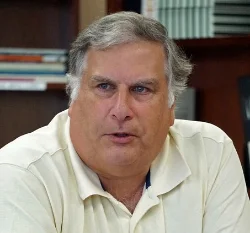

Mary M. Madden, Rhode Island Consent Decree Coordinator, left; and Ray Bandusky, Executive Director of the Rhode Island Disability Law Centerm right. Madden spoke about exceptions to the consent decree "employment first" policy at a recent meeting of the Employment First Task Force.

By Gina Macris

The 2014 consent decree designed to broaden employment opportunities for persons with developmental disabilities in Rhode Island doesn’t mean that everyone who receives adult services must work.

Yet the idea that there are no exceptions to the consent decree’s “employment first” philosophy has grown into a myth, resulting in considerable confusion and anxiety about the impact of the agreement on those who might not be suited for supported employment in the community.

The issue surfaced in several public forums in the past few months.

For example, in early April, state lawmakers heard from one of their colleagues about a man whose medical records listed 17 surgeries, and yet his family was told his support services for daytime activities would be cut off unless he looked for work.

A few weeks later, at a different forum, state officials were told about a 56-year old man who, according to his sister, doesn’t understand the concept of work. His family also was told he needed to look for work, or face loss of daytime support services.

In fact, the consent decree makes allowances for these kinds of cases. But it appears that its provisions are not well understood by the public, and in at least in some cases, by state employees assigned to help individuals with developmental disabilities and their families.

At a statewide meeting in late March, the organization Advocates in Action poked holes in several misconceptions about the consent decree with a series of wacky skits wrapped around the title “Mythbusters,” a take-off on the movie “Ghostbusters.” Advocates in Action, whose members are consumers of developmental disability services advocating for themselves, produced the show, with support from their peers and staff. The first myth they debunked was the “no-work/ no-funding” notion.

The topic of exceptions to the employment policy in consent decree came up most recently at the May 10 meeting of the Employment First Task Force at the offices of the Community Provider Network of Rhode Island (CPNRI) in Warwick.

The Task Force is a creature of the consent decree, which specifies that its membership must include representatives of consumers, families, and a variety of community organizations focused on developmental disabilities, like the Rhode Island Disability Law Center, the Sherlock Center on Disabilities at Rhode Island College, the Rhode Island Parent Information Network (RIPIN), and others..

The Task Force, whose membership does not include any representative of the state disability agency, is intended to serve as a resource for both government and the community.

At the May 10 meeting, the federal consent decree monitor, Charles Moseley, pointed out in a telephone conference call that the agreement does contain an “employment first” policy. The policy serves as the foundation for remedying Rhode Island’s violations of Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act, (ADA), which says that disability services and supports should be applied in the least restrictive setting that is appropriate for an individual.

The policy makes “work in integrated employment settings the first and priority service option” for adults with disabilities, according to the consent decree.

That said, both Moseley and the state’s consent decree coordinator, Mary M. Madden, agreed on the exceptions to the policy.

Madden, who attended the meeting in person, elaborated. She said individuals who say they don’t want to work will be asked to first participate in trial vocational and work experiences so they can later make an “informed choice” about employment.

If they ultimately choose not to work, they must apply for a variance to the “employment first” policy, she said, but if they are of retirement age, or have health and safety issues that prevent them from looking for a job, no variance is necessary.

Claire Rosenbaum, Adult Supports Coordinator for the Sherlock Center on Disabilities, said “nobody in the community” knows what the variance process is. The notion that certain individuals would be exempt from seeking a variance “is not being communicated at all,” she said.

Madden said “lots of people have significant health concerns. They may say, ‘my goal is to maintain my health’ and consider employment in the future.”

“If you’re in crisis, you’re not thinking about a job. Without the context of that information,” she said, “just talking about the variances” isn’t useful.

Madden was asked about the criteria for determining that someone has a medical or behavioral issue exempting the individual from pursuing employment. She said she didn’t know. “That work needs to be done very soon,” she said.

It’s complicated, she said. Some people have very complex disabilities who are nevertheless working, she said, “and you don’t want to take that off the table for someone.”

The consent decree required the court monitor and the parties to the agreement - the state and the U.S. Department of Justice - to “create a process that governs the variance process within 30 days” of the date the agreement was signed.

That signing date was April 8, 2014. The variance process still hasn’t been hammered out completely, although Madden indicated it would be finished over the summer.

One big unanswered question is the cost of providing services that are required as part of the variance process.

The consent decree says that to be in a position to make an “informed” choice about job-hunting, someone must first participate in a vocational assessment and a sample work experience, as well as receive education and information about employment and counseling about the effect of employment on disability benefits.

Madden, in a follow-up email, referred a reporter to Andrew McQuaide, Chief Transformation Officer at the Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals. Efforts to reach McQuaide Thursday and Friday May 12 and 13 were unsuccessful.

The dissemination of information about the “employment first” policy, as well as exceptions to it, was to have been part of a communications plan the consent decree required to be in place by Sept. 1, 2014, but like the variance process, the communications plan has not been finalized.

The plan, still in the works, is intended to provide public education and information about the decree and connect various segments of the developmental disability community with each other.

Moseley, the monitor, must approve it, and he has been asking for progress reports, most recently in a filing with the U.S. District Court.

At the task force meeting, Madden said “there is agreement in very general terms” on the plan.

Questions of cost and sources of funding have not been resolved for the communications plan, according Sue Donovan of RIPIN, who is familiar with it.

For readers wishing additional information:

Mary M. Madden, the state’s consent decree coordinator, has offered to answer questions about the consent decree via email, at mary.madden@ohhs.ri.gov or by phone at 527-2295.

· Here is variance language from the consent decree:

L. Any individual eligible for a Supported Employment Placement, but who makes an informed choice for placement in a facility-based work setting, group enclave, mobile work crew, time-limited work experience (internship), or facility-based day program, or other segregated setting may seek a variance allowing such placement. Variances may only be granted after an individual has:

1. Participated in at least one vocational or situational assessment, as defined in Sections II(11) and (16);

2. Completed one trial work experience, as defined in Section II(15);

3. Received the outreach, education, and support services described in Section X; and

4. Received a benefits counseling consultation, as described in Section IV(6).

M. If a variance is granted, the individual must be reassessed by a qualified professional, and the revised employment goal reevaluated, within 180 days, and annually thereafter, for the individual to have the meaningful opportunity to choose to receive Supported Employment Services in an integrated work setting. The Parties and the Monitor shall create a process that governs the variance process within 30 days of entering this Consent Decree.

N. Individuals who seek a variance from this Consent Decree, but who are unable to participate in a trial work experience, pursuant to Section V(L), due to a documented medical condition that poses an immediate and serious threat to their health or safety, or the health or safety of others, should they participate in a trial work experience, may submit documentation of such a condition to the Monitor to seek exemption from Section V(L)(2). Exemptions from trial work experiences will be subject to the Monitor’s approval.

O. The State will ensure that individuals currently in sheltered workshops who receive a variance pursuant to Section V(M) will continue to receive employment services.

The entire consent decree can be found at this link.