RI's New DD Services Begin Roll-Out

/Anne LeClerc Explains New Assessment Process in Virtual Meeting Via Advocates In Action RI

By Gina Macris

After years of looking the other way, the Rhode Island General Assembly has funded comprehensive reform of the state’s developmental disabilities services.

What the new system will look like to the people that it will serve – individuals with disabilities, their families and agencies that provide services – has yet to be fully fleshed out. State officials are putting the final pieces together and explaining the changes to the developmental disabilities community.

But the overall outline of reform is clear, and the state has hired additional staff to communicate the changes and help with implementation.

As of July 1, state officials have been given the money to do the job: a $78.1 million reform package proposed by Gov. Dan McKee and approved by the General Assembly last month.

Services for adults living with intellectual and developmental challenges are funded through the federal-state Medicaid program, with the federal government supporting slightly more than half the cost.

In all, the Division of Developmental Disabilities (DDD) will receive $469.1 million during the current fiscal year, nearly $92.8 million more than the final allocation for the budget cycle that ended June 30. The DDD spending ceiling makes up nearly 70 percent of a total budget of $672.8 million for the Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH.)

The new budget marks a watershed moment in the life of a federal court consent decree, signed in 2014 by then-Governor Lincoln Chafee and representatives of the federal Department Of Justice, which had filed suit to enforce the Integration Mandate of the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA.)

A Capsule History

The agreement committed the state to improve the quality of life of adults who had been warehoused in sheltered workshops or day care centers., in violation of the ADA’s Integration Mandate. Except in rare cases, such settlements cannot be appealed.

But it has taken another nine years of dogged federal enforcement, as well as emerging advocacy at the State House, for state government to come up with the necessary funding and reorganize the bureaucracy to turn the system around.

For years, the state’s powerbrokers paid lip service to the consent decree, setting up pilot programs that were never expanded and adding pennies to the poverty wages of workers in private agencies that did the day-to-day work of implementation. Staff attrition grew to be the number one problem in providing services.

Then in 2021, Chief Judge John J. McConnell, Jr. of the U.S. District Court, started ratcheting up the pressure, issuing one order after another that dealt with caregiver wages and other issues.

Under threat of a contempt finding and hefty fines, the state produced a comprehensive action plan for consent decree compliance, which McConnell approved in October, 2021.

The Role of Advocacy

A former court monitor in the case, Charles Moseley, once said that judicial action can go only so far. Enduring change depends on the advocacy of the people.

While consent decree case dragged on before Judge McConnell, the developmental disabilities community shifted strategy at the State House, joining forces with dozens of other organizations to send the message that the chronically underfunded developmental disabilities system was just a microcosm of all Medicaid health and human service programs in the state.

For State Sen. Louis DiPalma, who became chairman of the Senate Finance Committee earlier this year, all the coalition’s voices shine the light on broad inequities in healthcare and human services.

A law enacted in 2022 with the leadership of DiPalma in the Senate and Deputy Majority Leader Julie Casimiro in the House has tasked the state’s health insurance commissioner with revising Medicaid reimbursement rates every two years. The first set of recommendations is due out in the fall and will be waiting for the General Assembly when it convenes again in January.

Beginning in 2016, when DiPalma pushed back against an impractical plan to pay for the consent decree by cutting group home costs, he has gained prominence as an advocate for adults with developmental disabilities.

From his earliest days as a legislator, he said, he has sought equity for everyday Rhode Islanders based on “facts and data.” DiPalma has served in the Senate since 2009.

The Power of the Court

Key facets of the latest funding for developmental disabilities can be traced back to specific court orders that McConnell has issued in the last two and a half years –as well as recommendations from an independent court monitor, A. Anthony Antosh, appointed by McConnell.

An entry-level wage for direct care workers of $20 an hour, with an average rate of $22.14 an hour for more experienced caregivers. This pay bump, from a minimum of $18 an hour, costs $30.8 million, including $13.9 million in state funding, and the rest in federal Medicaid dollars. A court order issued Jan. 6, 2021 said the $20 rate must go into effect by Jan. 1, 2024.

An additional $44.2 million from Medicaid, including $20 million from the state, to increase flexibility in providing community-based services available to adults with developmental disabilities. Until the monitor spoke up in a court session earlier this year, the state had planned to continue providing 40 percent of daytime services in day centers. The increased funding authorizes additional staffing for community-based activities anytime of the day seven days a week.

$3.1 million, including $935,465 in state revenue, to reflect a last-minute projected cost increase for the developmental disabilities caseload calculated during the May Caseload Estimating Conference. (An earlier article citing $75 million in reforms did not take into account the results of the Caseload Estimating Conference.)

The Bureaucracy Matters

In the Caseload Estimating Conference, fiscal representatives of the House and Senate leadership and the governor convene with human services officials in public twice a year to do the math around the state’s public assistance obligations. There is a similar Revenue Estimating Conference.

The impetus for including developmental disabilities in caseload estimating came from one of Judge McConnell’s court orders.

Until developmental disabilities services were included in the Caseload Estimating Conference in November, 2021, budgeting for this segment of the population lacked transparency. Families and advocates approached each new session of the General Assembly with dread because of the uncertainty about sufficient funding.

Under the old system of service delivery, individual funding for adults with intellectual and developmental challenges – about 4,000 people - was made to fit into one of 20 boxes, and anyone who needed anything more had to file an arduous appeal.

Most of the appeals were granted, after service providers and families showed the individual really needed a particular service. But the added funding often lasted only for 12 months, and the appeal process began once again.

In the meantime, BHDDH officials were berated by lawmakers for constantly running budget deficits. At one point, BHDDH projected a $26 million deficit for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2018 because of extra individual funding granted on apppeal.

Changes Take Shape

During a recent interview, DiPalma, the Senate finance committee chairman, outlined additional features of the new state budget that will benefit all people with all kinds of disabilities:

Increased access to the Rhode Island Public Transit Authority’s (RIPTA’s) paratransit program through $500,00 in vouchers for people who live outside the geographical catchment area for this service. DiPalma said a lack of transportation often keeps people from getting a job or engaging in community activities.

Adoption of the Ticket-to-Work program, which removes limits on earnings of people receiving federal disability payments. This change is expected to boost enthusiasm among those who might fear losing benefits if they get a job.

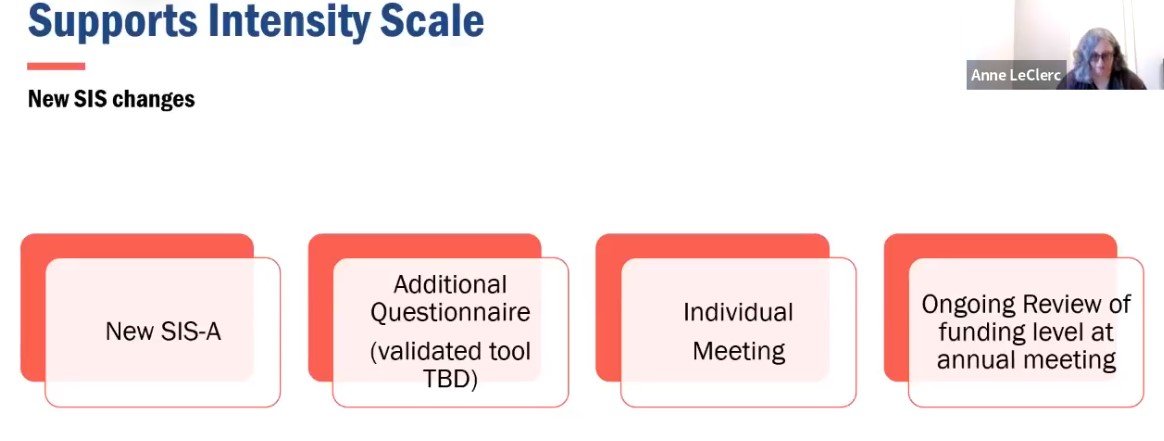

In the new system, individuals will get the funding and services they need “up front,” said Anne LeClerc, Associate Director of Program Performance at DDD during a virtual public forum last month.

The state will supplement its standard assessment with a questionnaire to draw out any needs that might have been overlooked, instead of allocating a cookie-cutter funding level and waiting for an appeal.

The new approach will “make it better for everybody,” LeClerc said. “And every year, we’ll be doing an ongoing review to make sure that the funding is appropriate,” she said.

Appeals will still be an option, but officials believe the new approach will cut the numbers down significantly, she said.

In another big change, individuals will no longer have to give up any services to get employment-related supports. Instead, the reforms will make job supports available to all who want them.

State officials have insisted they will fully comply with the consent decree by the deadline next June 30, but even the rapid changes being made today probably will not be fast enough to meet the deadline.

LeClerc and others admitted it will take a year to phase in all the pieces of the new model with everyone eligible for services.

For example, LeClerc said the questionnaire intended to draw out any supplementary needs not captured in the basic assessment hasn’t been finalized yet. And the latest version of the assessment itself, revised by American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities during 2022, has not yet been put into use in Rhode Island.

While the interviewers have been trained in the new model, DDD officials indicated the revised assessment would not roll out until August at the earliest.

LeClerc said the state will need to collect the data from 500 assessments before it can devise a new funding formula.

The DOJ has said it requires at least a year’s smooth implementation of court-approved changes before it signs off on a consent decree.

A DOJ lawyer, Amy Romero, warned the state last December that it needed to bring a sense of urgency to its efforts to meet the deadline for full compliance, even as she praised officials’ stepped-up efforts in 2022.

Antosh, the independent court monitor in the case, is expected to file his assessment of the state’s latest efforts before the end of July.

DDD Expands Staff

To help with implementation of the consent decree, DDD has filled a year-long vacancy in the administrative position dedicated to employment-related support and made several other appointments. The budget sets aside $203,275 for eight new permanent positions dedicated to the consent decree.

Elvys Ruiz, who has more than 20 years’ experience in state service, was hired in May as Administrator for Business and Community Engagement. A native of the Dominican Republic, he is a former interim administrator of the Minority Business Enterprise Compliance Office at the Department of Administration and also has experience at the Department of Human Services and the Department of Transportation. Ruiz succeeds Tracey Cunningham, who left more than a year ago.

Six new DDD staffers also were introduced at the virtual public forum in June, including at least one who will be working directly with individuals and families who direct their own program of services, a segment that makes up one quarter of the caseload.

Amethys Nieves was hired in May as Associate Administrator of Community Services to work on improving information and communication. She has degrees in psychology and social work and has experience and has experience in providing direct services and in development of healthcare programming.

Johanna Mercado and Jackie Camilloni also have been hired as part of a communications team as coordinators of Community Planning and Development, with Camilloni focusing on individuals and families who direct their own services, a group that now makes up about 25 percent of the developmental disabilities caseload. Mercado is an academic librarian with degrees in political science and library science. Camilloni has 25 years’ experience at a privately-run organization serving adults and children with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD). She also has worked as a state social worker at both the Department of Children, Youth and Families and DDD.

Steven Seay is the new Coordinator of Integrated Community Services. He has worked in the human services for thirty years, with experience in developmental disabilities, nursing home social services, and adult protective services. Most recently, he worked in DDD’s Office of Quality Improvement.

Kelly Peterson, a former DDD social worker and supervisor, has been hired as the new Chief of Training, Staff Development and Continuous Quality Improvement to oversee changes in professional practice required by the consent decree. She also has worked as a DCYF social worker.

Peter Joly, who has worked in the mental health field for more than 20 years, has been hired as a Principal Community Development and Training Specialist. He also has experience providing services for adults with developmental disabilities.

Cynthia Fusco, chief assistant to DDD director Kevin Savage, has been promoted to a new position as Interdepartmental Project Manager.

Next Steps

Judge McConnell has scheduled a public status hearing Tuesday, Aug. 1 at 10 a.m. The hearing will be accessible remotely. (He will meet with lawyers in chambers in late September, but that session is closed to the public.) To watch the August 1 hearing, go to the Court’s calendar page, enter the date of the hearing and select Judge McConnell’s name from the drop-down menu of judges. Click on “Go” to get to a link to instructions for public access to the hearing.

DDD, meanwhile, is holding in-person and virtual public meetings where officials have said they will add greater detail to the overview of the new system they outlined June 20.

A video recording of the June 20 public forum is on the Facebook page of Advocates In Action RI

Three informational sessions remain in July:

Wednesday, July 19, 2023 5:00 PM to 6:30 PM, Rochambeau Library Community Room 708 Hope St, Providence

Tuesday, July 25, 2023 1:00 PM to 2:30 PM, Warwick Public Library Large Meeting Room 600 Sandy Lane, Warwick

Virtual public meeting Thursday, July 27, 2023 3:00 PM to 4:30 PM. Click here to register via Zoom.